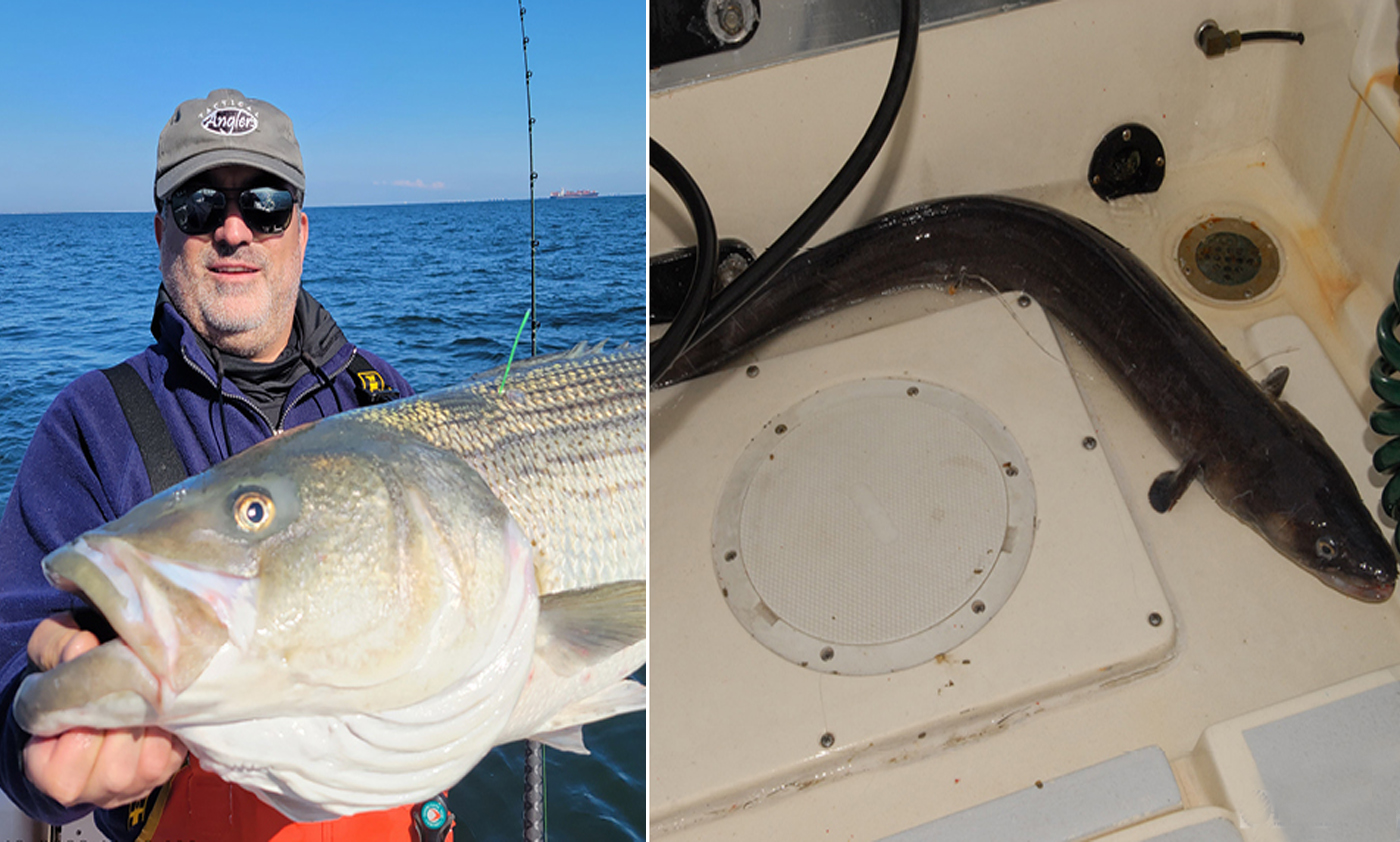

If you fish for striped bass or cobia then you are probably acquainted with the American eel because it is a favorite snack of both species. You’d be hard pressed to find something to put in the water that has a better chance of attracting a bite from either gamefish. Three of the last IGFA® All-Tackle World Record striped bass caught between Charles B. Church’s 73-pound bass in August of 1913 and Greg Myerson’s 81-pound, 14-ounce current record holder fell for live eels. And nothing gets a quicker reaction from a pod of cobia playing hard-to-get than putting a live eel in their midst. You can cast them, drift them, fish them shallow or deep, day or night. Old timers fished dead eels on a tin squids to make it swim or used eel skins sewn over wood swimming plugs. A more recent technique has been catching stripers over 50 pounds more frequently than all the other techniques combined. It consists of slow trolling a spread of live eels using side planers and floats, and it attracts big bass like kids to Halloween candy.

With all the ways anglers can use eels to catch fish, very few know that eels are one of the most mysterious creatures found on the planet and one of the most over-exploited. They have an incredibly complicated life cycle which makes tracking the health of the resource difficult at best. Most fishermen know that salmon, striped bass, shad, steelhead and river herring are anadromous. That means they live most of their adult lives in saltwater but reproduce in freshwater. They swim into rivers and streams to lay their eggs, and the young spend some portion of their early life in freshwater or estuarine areas. Eventually, the younger fish join the mature members of their clan in the ocean only returning to freshwater to repeat the cycle. Some anadromous fish can spawn many times during their life span, stripers are a prime example, and others die after spawning just once, like Pacific salmon.

Somewhere along the evolutionary ladder the eel got its signals crossed because they do the whole saltwater-freshwater thing in reverse, and they carry it to incredible extremes. Put in the simplest form, eels spawn and their young spend the earliest portion of their lives in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean in an area called the Sargasso Sea, about as far away from land as you can get. Located between Bermuda, the West Indies and the Azores, this area of the Atlantic is at the vortex of the massive North Atlantic currents that drive the ocean’s circulation. These rivers of current move in a clockwise direction around the outer rim of the ocean. The Gulf Stream is the western current that pushes from south to north and eventually across the North Atlantic, where it meets the Canary Current that pushes from north to south toward northern Africa. There it turns back to the west along the equator completing the circuit.

Into this desolate area of the ocean, sexually mature eels from North America, Europe and the Mediterranean congregate to mate, spawn and die. From billions of fertilized eggs hatch the leptocephalus or larvae that float along with the currents, but during this life stage they don’t look like eels. The only thing that stands out on a larval eel is its eyes because the rest of its body is clear. This cloak of invisibility is their only protection from predation until they arrive at their future coastal environments. They feed on zooplankton and hide among the drifting Sargasso weed, growing slowly. Along the way they take on the shape of a tiny mature eel but remain transparent, eventually drifting to the outer edge of the currents. They have no influence on where they will end up because they are totally dependent on the vagaries of the Atlantic currents, and they have just as much chance of being deposited along the coast of France or Spain as they do the coast of the United States or Canada. All they know is once they get close to coastal waters it’s time to get their transparent little tails in gear and swim towards shore where they enter estuaries, tidal streams and rivers. Numbering in the many millions they arrive in the spring. The tiny eels are still clear, only a couple of inches long and as old as three years by this time. At this stage of their life cycle, they are called glass eels for obvious reasons. It was at this stage that their numbers were decimated in the 1970’s and 1980’s by dip netters who walked the stream banks of North America from the Mid-Atlantic to Nova Scotia, capturing them by the buckets-full to sell them into bondage. Most ended up in Asian countries where they would be raised in ponds until they were large enough to ship to market because eels are considered a delicacy in many areas of the world. The glass eel fishery in the United States was unregulated until the late 1990’s when some states banned the practice altogether and the remainder strictly regulated the fishery.

A glass eel is neither male nor female. It is gender neutral with an unknown preferred pronoun. To transform into either sex, the determining factor seems to be where it goes once it reaches the coast. Glass eels that continue into freshwater to spend the next couple of decades in lakes and rivers become females. Eels that remain in an estuarine environment become male. And they don’t meet up again until they prepare for that long, once-in-a-lifetime swim to the middle of the Atlantic Ocean to make the ultimate sacrifice for their species.

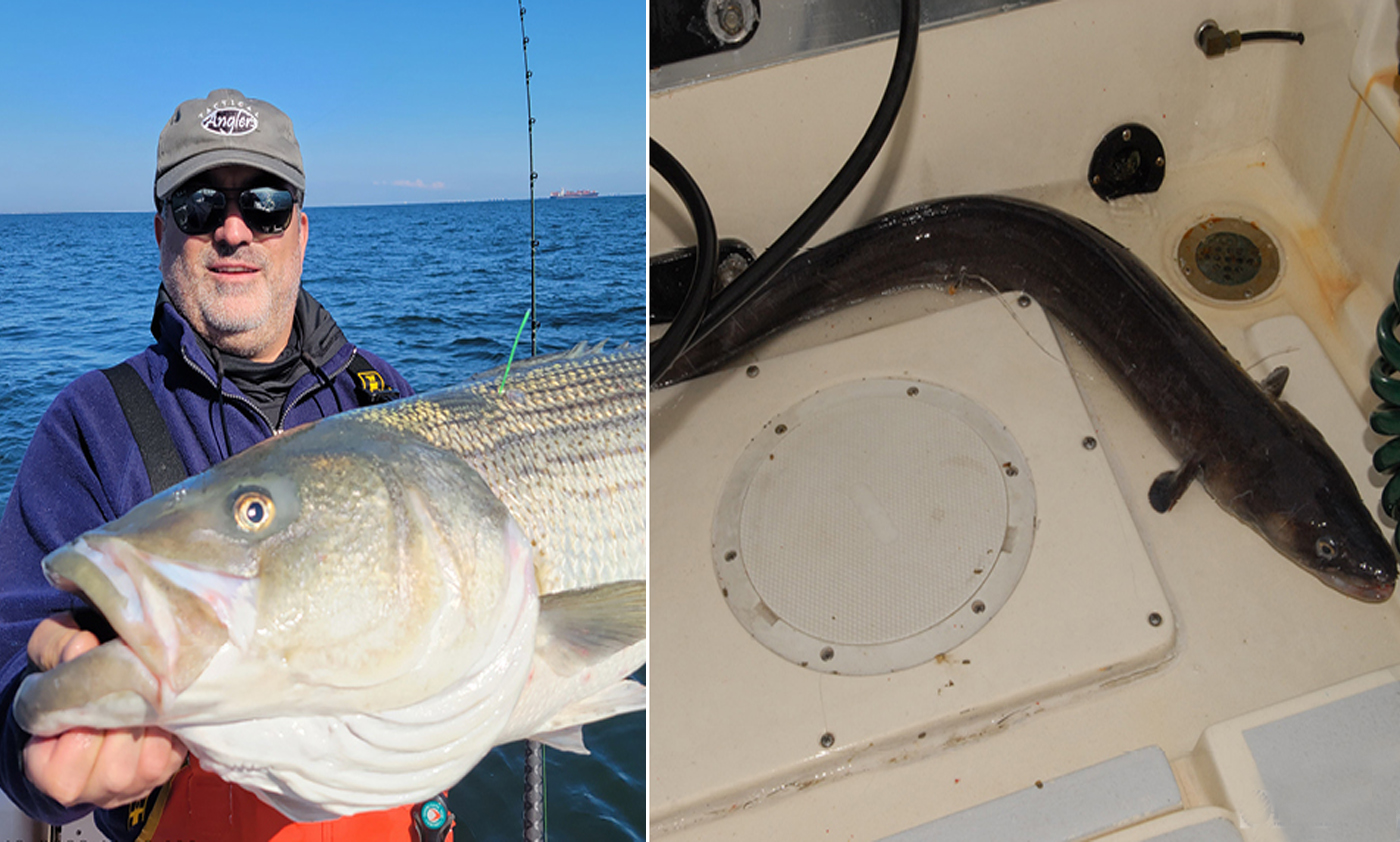

After a short while in fresh or tidal waters the glass eels lose their cloak of invisibility and take on a dull greenish hue, becoming elvers. As they get larger, female eels will take on a yellow and green coloration and the moniker yellow eels. Mature male eels vary in color from near black to green until they get large enough to beginning thinking about heading offshore for the last round up. As they grow their bodies undergo other physiological changes, the most noticeable is the enlargement of their eyes. As their eyes become more prominent, they transform from daytime feeders to larger night stalkers and while they have no teeth to speak of, they are accomplished predators as well as scavengers.

When they reach maturity females change color again. Their backs become darker, turning to hues of black and purple that offsets a silver-white belly, and their entire body takes on an iridescent sheen. Now fully mature they are called silver eels, and they are ready to begin their run back to the sea, a journey that can span over a thousand miles through rivers, swamps, and lakes and even across wet fields before they ever reach the ocean. As they near saltwater the females undergo an internal chemical change that allows them to tolerate breathing saltwater again, a change the males do not require because they never left the tidal environment. By now the females can range in size up to four feet in length and seven pounds in weight, while the males rare exceed two feet long. Together they head offshore, using some unknown guidance system that leads them back to their ancient spawning grounds many hundreds of miles out in the Atlantic. There they congregate with millions of other members of their clan from around the Atlantic basin in a final effort to reproduce and replenish their kind. When that is done, they will sink slowly into the ocean depths and die.

Maybe after reading this, the next time you pick up and eel to impale it on a big old circle hook to entice a hungry striper or cobia, you’ll remember what remarkable creatures they really are and the incredible journey that slimy, squirmy little thing accomplished just to get that far in its long but undistinguished life. There is still so much science doesn’t understand about the lowly eel, but we know they make really good bait.

Back to Blue Life

With all the ways anglers can use eels to catch fish, very few know that eels are one of the most mysterious creatures found on the planet and one of the most over-exploited. They have an incredibly complicated life cycle which makes tracking the health of the resource difficult at best. Most fishermen know that salmon, striped bass, shad, steelhead and river herring are anadromous. That means they live most of their adult lives in saltwater but reproduce in freshwater. They swim into rivers and streams to lay their eggs, and the young spend some portion of their early life in freshwater or estuarine areas. Eventually, the younger fish join the mature members of their clan in the ocean only returning to freshwater to repeat the cycle. Some anadromous fish can spawn many times during their life span, stripers are a prime example, and others die after spawning just once, like Pacific salmon.

Somewhere along the evolutionary ladder the eel got its signals crossed because they do the whole saltwater-freshwater thing in reverse, and they carry it to incredible extremes. Put in the simplest form, eels spawn and their young spend the earliest portion of their lives in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean in an area called the Sargasso Sea, about as far away from land as you can get. Located between Bermuda, the West Indies and the Azores, this area of the Atlantic is at the vortex of the massive North Atlantic currents that drive the ocean’s circulation. These rivers of current move in a clockwise direction around the outer rim of the ocean. The Gulf Stream is the western current that pushes from south to north and eventually across the North Atlantic, where it meets the Canary Current that pushes from north to south toward northern Africa. There it turns back to the west along the equator completing the circuit.

Into this desolate area of the ocean, sexually mature eels from North America, Europe and the Mediterranean congregate to mate, spawn and die. From billions of fertilized eggs hatch the leptocephalus or larvae that float along with the currents, but during this life stage they don’t look like eels. The only thing that stands out on a larval eel is its eyes because the rest of its body is clear. This cloak of invisibility is their only protection from predation until they arrive at their future coastal environments. They feed on zooplankton and hide among the drifting Sargasso weed, growing slowly. Along the way they take on the shape of a tiny mature eel but remain transparent, eventually drifting to the outer edge of the currents. They have no influence on where they will end up because they are totally dependent on the vagaries of the Atlantic currents, and they have just as much chance of being deposited along the coast of France or Spain as they do the coast of the United States or Canada. All they know is once they get close to coastal waters it’s time to get their transparent little tails in gear and swim towards shore where they enter estuaries, tidal streams and rivers. Numbering in the many millions they arrive in the spring. The tiny eels are still clear, only a couple of inches long and as old as three years by this time. At this stage of their life cycle, they are called glass eels for obvious reasons. It was at this stage that their numbers were decimated in the 1970’s and 1980’s by dip netters who walked the stream banks of North America from the Mid-Atlantic to Nova Scotia, capturing them by the buckets-full to sell them into bondage. Most ended up in Asian countries where they would be raised in ponds until they were large enough to ship to market because eels are considered a delicacy in many areas of the world. The glass eel fishery in the United States was unregulated until the late 1990’s when some states banned the practice altogether and the remainder strictly regulated the fishery.

A glass eel is neither male nor female. It is gender neutral with an unknown preferred pronoun. To transform into either sex, the determining factor seems to be where it goes once it reaches the coast. Glass eels that continue into freshwater to spend the next couple of decades in lakes and rivers become females. Eels that remain in an estuarine environment become male. And they don’t meet up again until they prepare for that long, once-in-a-lifetime swim to the middle of the Atlantic Ocean to make the ultimate sacrifice for their species.

After a short while in fresh or tidal waters the glass eels lose their cloak of invisibility and take on a dull greenish hue, becoming elvers. As they get larger, female eels will take on a yellow and green coloration and the moniker yellow eels. Mature male eels vary in color from near black to green until they get large enough to beginning thinking about heading offshore for the last round up. As they grow their bodies undergo other physiological changes, the most noticeable is the enlargement of their eyes. As their eyes become more prominent, they transform from daytime feeders to larger night stalkers and while they have no teeth to speak of, they are accomplished predators as well as scavengers.

When they reach maturity females change color again. Their backs become darker, turning to hues of black and purple that offsets a silver-white belly, and their entire body takes on an iridescent sheen. Now fully mature they are called silver eels, and they are ready to begin their run back to the sea, a journey that can span over a thousand miles through rivers, swamps, and lakes and even across wet fields before they ever reach the ocean. As they near saltwater the females undergo an internal chemical change that allows them to tolerate breathing saltwater again, a change the males do not require because they never left the tidal environment. By now the females can range in size up to four feet in length and seven pounds in weight, while the males rare exceed two feet long. Together they head offshore, using some unknown guidance system that leads them back to their ancient spawning grounds many hundreds of miles out in the Atlantic. There they congregate with millions of other members of their clan from around the Atlantic basin in a final effort to reproduce and replenish their kind. When that is done, they will sink slowly into the ocean depths and die.

Maybe after reading this, the next time you pick up and eel to impale it on a big old circle hook to entice a hungry striper or cobia, you’ll remember what remarkable creatures they really are and the incredible journey that slimy, squirmy little thing accomplished just to get that far in its long but undistinguished life. There is still so much science doesn’t understand about the lowly eel, but we know they make really good bait.